This week I’ve received some emails from university students keen to discuss the Environmental Audit for assignments they’re working on.

One of these students, “M.” is studying for a Masters of Arts in Creative Writing.

Here’s her message, with my response below…

Hi Lucas.

I have been following your Environmental Audit online and at the MCA and I’m captivated by the self-referential nature of your work — something which I believe is vital for eco-artists.

I am a Masters of Arts Student and I have chosen to do my ‘open-essay’ on eco-art and public action. It’s a small piece worth 1500 words and will be shown to the class, in a workshop, and to my convener.

I wanted to know:

- Are your works meant to be a catalyst for debate? Or, for change? This is particularly interesting to me because of their interactive nature. Are you seeking to enter your audience into discourse about environmental concerns and into a dialogue with each other?

- In other words, do you intend for your audience to enter into discourse about the use of energy/resource in the exhibition and eco-art movement? Or is there a desired path-of-action you wish to catalyse?

- Is provoking thought, and creating conversation/discussion, enough for our planet?

- Do you feel that your project ‘belongs’, in some manner, to society because it engages with the public sphere, with issues of the public and of their space?

- Is your work — conceptually and physically/technologically — accessible?

- Does environmental art need to be self-referential, and exhibit an acute awareness of medium and sustainability, to hold any value in the enviromission?

- If eco-artists don’t specifically intend to activate change in their audience, then is environmental art essentially ‘art for art’s sake’ where the creators simply leach off of the green franchise?

I look forward to hearing from you.

Regards,

M.

Thanks M. Some of these are big questions. Let’s see how I go.

With regard to your first 2 questions, I think that catalysis is not a bad metaphor. A catalyst increases the rate of change in a chemical reaction. With my Environmental Audit project, I’m hoping to do a similar thing. But rather than accelerating chemical change, I am hoping to accelerate social change.

This sounds lofty and ambitious and a bit pretentious. However, I should follow this statement with the understanding that I am not actually in a position to persuade anyone into changing anything (and I think this is probably pretty clear to anyone reading this blog). I am neither particularly clever, nor exemplary in my own lifestyle. And I don’t hold a position of any power to execute decisions affecting anyone except myself.

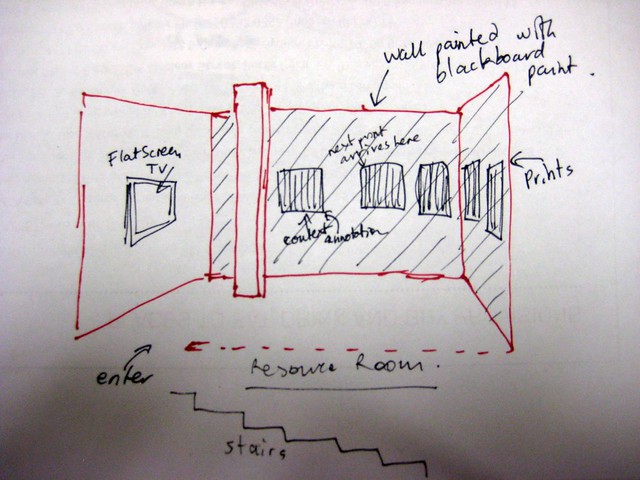

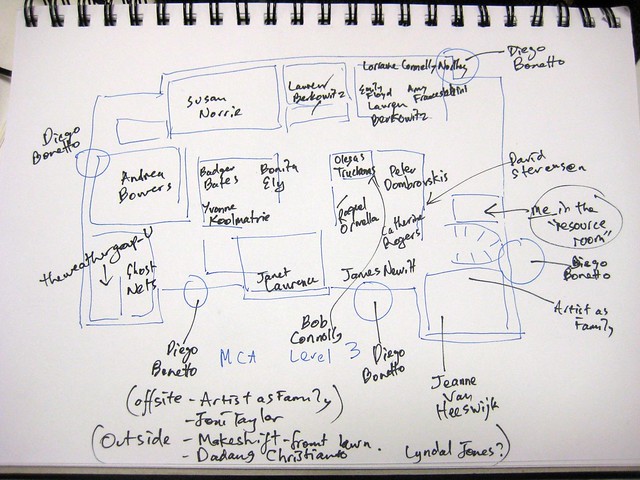

What I can do, though, is to publically examine myself, and the very local situation in which I find myself: an environmentally-themed exhibition at a contemporary art gallery. The players in this game are the artists, curators and gallery-workers, visitors and blog readers; and the set of relations between them, the organisations we belong to, and the materiality of the planet we’re a part of.

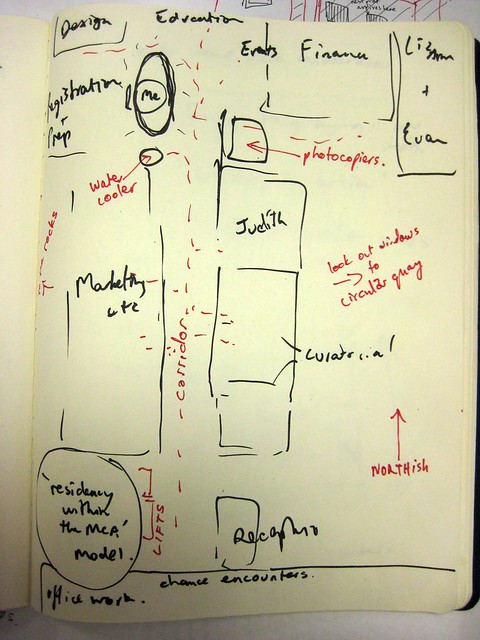

I have the privelege of spending 3 months of my life dwelling on (and in) this situation. I also have the luxury of operating out of a highly visible piece of real estate (on the third floor of the MCA), and these things may amount to some degree of power to activate change, under the (possibly erroneous) equation “visibility is relevance”.

So I am hoping that my extended, open-ended, publically visible examination of this situation might lead to something shifting. But I have no fixed goal or particular idea as to what that shift might be.

To answer your third question: clearly, no. Provoking thought and discussion is not enough for our planet. We’ve got to actually do something too, something practical and something physical. The fact that endless discussions are not held to be enough is clear from the widespread derision which followed Julia Gillard’s pre-election announcement of a citizen’s assembly to discuss what to do about climate change.

But what to do, of course, is the question? How to do something when big changes seem to be in the hands of large corporations and governments? What do we do with our sense of impotence around this? In the first instance, we think and talk about it a lot. Then we start to group ourselves together and make small changes. None of these small changes (using energy saving bulbs, making compost, installing dual flush toilets, switching to recycled paper, planting vegies, keeping chickens, chaining oneself to a tree, voting in a federal election, writing a blog, blah blah blah) is going to “save the planet”. But I reckon that what we’re doing, when we make them, is preparing the soil for the big top-down changes to properly take root when they’re finally planted.

Question 4: Yes, the project “belongs to society”, in two ways. First, it takes place in society: its site is the public sphere itself (an online project unfolding over time, as well as interactions taking place in the semi-public sphere of the gallery). Second, its subject matter is specifically the social: How do the structure of our societies create situations which make large-scale environmental action difficult?

With regard to Question 5: perhaps you (and other readers) can answer this better than I can. All I can say is that I have attempted to be as clear as possible, within the project, about what the project is about, and what it is trying to do, and how – as well as to articulate my own limitations. I deliberately set out to avoid obfuscating and mystifying (and I am aware that contemporary art is often accused of such crimes). There are, of course, barriers to access: my project only uses English language; you have to be able to access the internet, and to navigate your way around a blog (and I know some older folks will have difficulty with this)…

Question 6: Not all art is overtly self-referential, nor does it need to be. That just happens to be the method of my own project right now. However, I think wilful naivety is going to be viewed more and more critically in years to come. By this I mean projects which don’t seem to have any awareness of the embodied energy and pollution inherent in their own materiality. (On the other hand, there is always the opposite possibility, where the mindless race towards armageddon may accelerate itself, as in this micro example from The Artist as Family’s Meg.)

With your seventh question, I see what you’re getting at but I don’t think it’s quite that simple. Intentionality is not the ultimate criterion by which we judge an artwork. Sometimes the artist’s intention can be completely superseded by the way an audience member might interpret or use it for a different purpose. So we have to zoom back a bit and see the work of art as a series of relationships which is far more complex than even the artist can know.