“My husband will drive miles for a cheap tank of petrol”.

– (something I overheard in the late 1990s…)

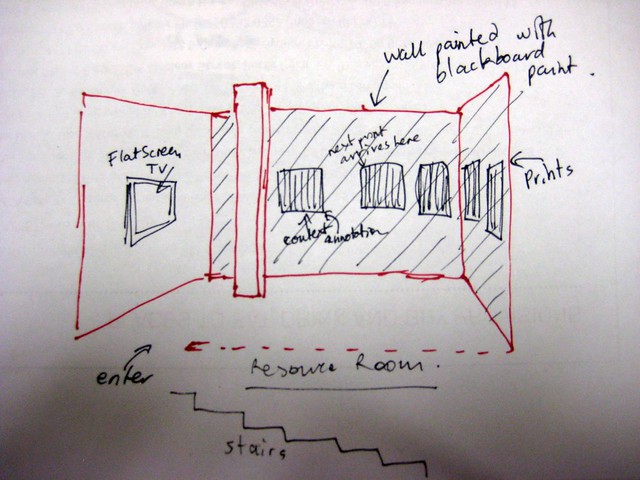

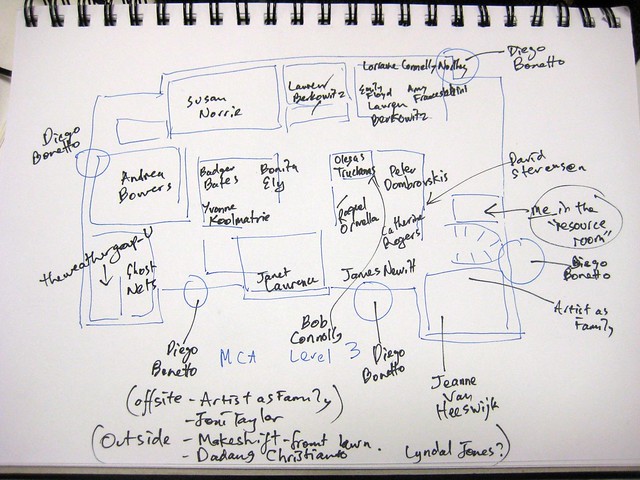

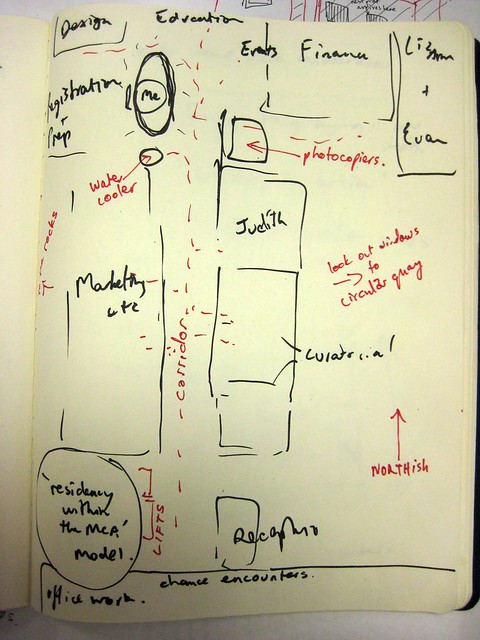

The prints that I will be producing, week-by-week, for the In the Balance show at the MCA will feature diagrams – some by me, some collaboratively drawn with other artists or museum workers.

They’ll be printed on the Big Fag Press – our salvaged offset-lithographic proofing press which now lives in Woolloomooloo. I’ll report more on the operations of the Big Fag soon enough. But today, my adventures were about paper.

What paper should these diagrams be printed on?

Obviously recycled, right?

And unbleached and so on.

And preferably made locally, rather than shipped halfway around the world.

Aesthetically, I have been thinking about a particular kind of paper called “bulky-news”. It’s like newspaper, but thicker and rougher. So it’s substantial, but it still has that scrapbook feel about it. And it’s greyish rather than pure white. I reckon this sort of thing would be good for communicating the “provisional” feel that I hope my printed diagrams will bear. Like, you could pick up a texta and start amending them, rather than feeling intimidated by the “fine-art”-ness that a more expensive-looking paper could communicate.

So today I headed out to the north side of the Harbour Bridge, to visit S&S Wholesales, who I’d been tipped off as a good source of bulky-news.

It turns out that this adventure was a bit of a wake-up call for me. At first, the nice ladies in the office-warehouse didn’t know whether their bulky-news was recycled. They looked it up, but there was no info to confirm nor deny. Nor was there anything in the documentation about where it’s made. One of the ladies offered to contact the supplier for me, saying she’d pass on whatever she discovered. But she warned me not to believe everything I hear about recycled paper. Sometimes, she said, it involves the use of more resources and energy than good old-fashioned straight up Paper.

Standing there in the paper warehouse, I felt a bit foolish – like my belief in the virtues of recycled-everything were somehow naïve… like it was a marketing ruse that had been sold to me and my do-gooding friends.

Whether or not this challenge was well-informed; whether or not my easily-crumbling confidence was too fragile, I don’t yet know. But it did make me realise that I need to do a bit more research about where paper comes from, and what’s involved in its manufacture. It did occur to me, too, that from a business perspective, S&S could probably benefit from thinking about the marketability of the widespread desire for “recycled” stuff. As I told her, folks are usually happy to pay more for it (even if we’re totally ignorant of the real story).

Incidentally, one of the artist groups that’s exhibiting in the In the Balance show is the Euraba Papermakers from North-West NSW. They’ll be in Sydney for a few days after the exhibition opens, running some workshops down at the Redfern Community Centre. I’m pretty sure their stuff is made out of offcasts from the cotton industry. Here’s a great yarn about how they got started up:

We thought: “Let’s make our own paper. It can’t be too difficult.”

We set up a back yard mill. In half a forty-four gallon drum, we cooked everything from scotch thistle to sunflower stalks.

On the verandahs of my house the women loudly pounded the washed cooked fibres with the amputated legs of old school chairs. Our vat was my infant daughter’s baby bath and we couched onto merino wool blankets (an engagement gift from my marital bed). After a homemade pressing, with river rocks and human bodies providing the pressure we dried the sheet of paper on the clothesline. The papers were cockled and attacked by curious Lousy Jack Birds.

Our first papers were chunky shingles, veggie felts formed with a production motto of “if you can’t see the fibre the sheet won’t survive.”

Paul West 2001

I guess the thing I love about this Euraba story is that it reveals the sort of intimacy with materials which comes from making it yourself, or at least knowing what went into its making. Whereas my warehouse experience was about something quite different: shipping goods around based on product codes rather than any kind of knowledge.

So anyway… having made the effort to go all the way to the S&S warehouse, I did buy some of their nice (but probably not recycled) bulky-news.

However, my quest for the perfect paper continues.

Glenn: We should give staff and museum visitors the option to walk up the stairs during the exhibition. (Currently, floors 3-6 of the MCA can only be accessed by the lift – how much power does this use per journey? More homework for me…)

Glenn: We should give staff and museum visitors the option to walk up the stairs during the exhibition. (Currently, floors 3-6 of the MCA can only be accessed by the lift – how much power does this use per journey? More homework for me…)