After making a great start (thanks to Louise the Intern) on Great Third Floor Lighting Survey, I discovered that I needed to dig deeper… So last week I spent some time with Mark and Nicki, both MCA preparators, both experts in the fields of A-V technology and lighting respectively.

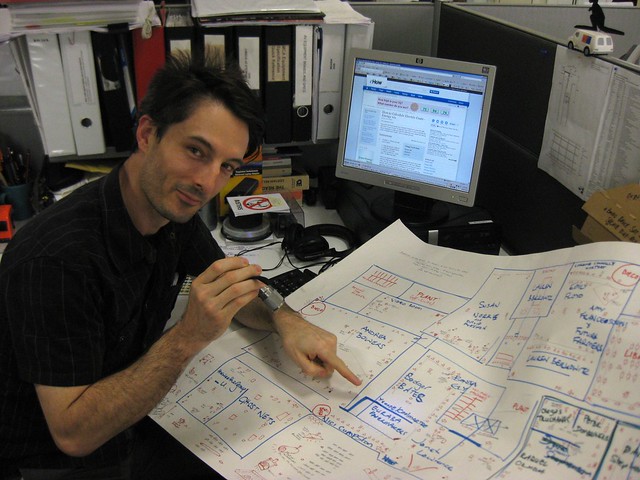

Here’s Mark, painstakingly working through each and every annotated video projector, LCD screen, DVD player, Macintosh computer and miscellaneous doohickey from our survey chart:

Mark is an artist. He has a particular interest and enthusiasm for this Audit project, partly because he’s insatiably curious about the behind-the-scenes workings of art galleries.

In fact, this is precisely what his own art practice is based upon: scraping away layers of time in an archaeological/cultural excavation. His work often results in some hidden aspect of the gallery being made visible (or audible). What lies behind hundreds of layers of paint? What does the relative humidity of the room sound like if it is translated into an audio signal? You can delve more deeply into his explorations here and here.

One of the things that’s happened in the past month while I’ve been on-site at the MCA is that Mark and I occasionally have small chats as we pass by each other on the way to the lift or the loo. Unique amongst his colleagues, Mark views my Audit project primarily through the lens of institutional critique: that quaint and arcane field of contemporary art whose main area of interest is exhibition and museum practices themselves. I want to spend a small moment thinking about this now…

According to the trusty ole wiki, Institutional Critique is an art practice which “seeks to make visible the historically and socially constructed boundaries between inside and outside, public and private” of the art world itself.

A classic example of this is Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, which revealed the dense network of questionable business dealings of shady businessman Harry Shapolsky. The exhibition was cancelled before it even opened.

According to some, “It was speculated that Shapolsky’s friends on the Guggenheim’s board of trustees were responsible for the cancellation although the allegation was never proved“. The point here, of course, is that Haacke’s work succeeded precisely in being shut down: the act of cancellation revealing the network of influences between Shapolsky and the museum in a powerful and practically demonstrated way.

There has been much discussion in recent years about whether Institutional Critique has now been co-opted by the institutions themselves. Considered in this way, Environmental Audit, while perhaps a critique of the MCA’s status-quo (in that it reveals some less-than-perfect aspects of the way the museum functions), is a weak shadow of Haacke’s seminal work, which struck a mitey blow at the Guggenheim in the early seventies. On the other hand, the very fact that the MCA has commissioned this critique is an public performance of its fundamentally progressive nature.

And so on. But for now, I should leave Simon Sheikh and his cronies to debate this, and get back to the point at hand!

…Which is that with Mark’s help, I managed to get a relatively accurate wattage for all those video projectors, amps and televisions which prop up the In the Balance artworks.

Combined with a similar painstaking process in which Nicki helped me to annotate the wattage of every light fixture in the exhibition, Louise and I should be able to crunch this information to work out a total power consumption for the whole show.

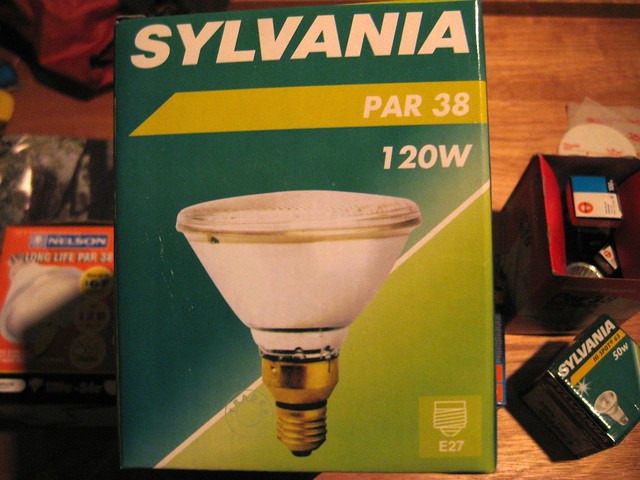

By the way, here are a few of the many fixtures Nicki showed me during the lighting survey. As you can see, they’re mainly old-skool, big wattage bulbs like this fella:

(There’s a whole other fascinating and thorny story to be told about the world of lighting, and the MCA’s impending conversion to low-wattage LED fixtures, but I’m going to leave that for another day…)

When we’d nearly finished this process, Mark looked very troubled. “You know”, he said, “all these projectors and halogen globes must have a significant impact on the operations of the air conditioning system”.

We looked at each other in silence. I knew it was true. If you’ve ever sat next to a 500 Watt video projector, you will know how much heat it puts out. What we realised, carrying out this electrical wattage survey, is that you can look at lights and projectors as illumination devices, in order to tally up the total power consumption of the exhibition infrastructure. But if you look at them in a different way – from the point of view of the museum’s air conditioning systems, then you begin to see them not in the service of lighting and visualisation, but as heating machines.

And so the cascading effects of one element upon another continue to wield their confounding force!

I was, however, heartened to be reminded of something told to me by Chris Arkins, an engineer who works for Steensen Varming, when I went to visit him a month or so ago. (Chris is currently consulting with the MCA on environmental initiatives incorporated into the development of the museum’s new building extension). I asked Chris for some advice on how to carry out my audit. “Lucas, if there’s one thing I can suggest, it’s this”, he said. “Set yourself some boundaries, or else you’re going to go completely mad”.

So in the spirit of this sage suggestion, I proposed to Mark that we consciously “bracket out” the influence of the heat produced by the lights and projectors. Such heat thus becomes a factor “not presently taken into account, but of which we are aware”. Perhaps – although I have no idea how – we could take this factor into consideration in my next mini-project: The Dreaded Heating, Cooling and Humidification Survey…

Is that the handsomest man in AV?

Anonymous: it certainly could be! Although it must be said that his good looks are only the icing on the cake: it’s his intimidating competence and dedication to the task at hand that makes him an asset to the organisation!

If Mark is responsible for the six mp3’s of artist talks for the “In The Balance” exhibition, please let him know that he owes me a beer for chewing up my expensive wifi connection :/ Please consider making the files smaller in future (up to 8 times smaller is possible).

It may have been a simple mistake but it is wasteful to encode them at 256kbps as he did. There is no way in the world anyone listening on headphones can hear the difference between that and 128kbps which would result in files half the size. The Bienalle MCA audio tour was a comfortable 64kbps (half the size again!) which is also the preferred bitrate on Radio National. I even would suggest that (if done properly) 32kbps is enough.

Obviously to be writing this I have more time on my hands than cash for my prepaid wireless, but seriously I just would not want others discouraged from making the most of your great idea to provide mp3’s (and many of them will be downloading via their phones when they are at the MCA).

Thanks for the heads-up, Poor Wireless User.

I’ve passed your message along to the MCA. I think Mark isn’t the fellow who owes you a beer though, it might be someone else in the organisation!

Curiously, at the same time you posted your comment, I got an email from my friend the artist Keith Armstrong, who has for a few weeks been badgering me to address the issue of the environmental footprint of computers and online downloads (a hidden component of my own project).

Keith writes:

In related matters – Keith also referred me to the Coltan Wars in the Congo – conflicts which have largely been funded by the profits gained from columbite–tantalite metallic ores from which many of our electronic components are manufactured.